Modern Thought | Cities, Spirituality and Tech Megacorps

Are Civilization and Income Inequality Inextricably Intertwined? (LitHub)

Piketty, who is “arguably the world’s leading expert on income and wealth inequality,” according to Nobel laureate Paul Krugman, has concluded that income inequality in the United States today is “probably higher than in any other society at any time in the past, anywhere in the world.” Such disparities of wealth are not just inhumane, they are inhuman, offending our innate predisposition for fairness.

The more we learn about foragers, the clearer it becomes that their lives are more approximate expressions of human nature than ours are, in that modern market capitalism requires an array of subversions of our natural behavior. “The view of human nature embedded in Western economic theory is an anomaly in human history,” Gowdy concludes. “The hunter-gatherer represents ‘uneconomic man.’”

Don’t miss the next Modern Thoughts!

Subscribe below.

Dread Scott’s Rebellion (Vanity Fair)

When Scott decided to reenact a slave rebellion, he had Nat Turner and Denmark Vesey in mind. Like most Americans, he had never heard of the 1811 uprising that erupted on the young country’s frontier. The rebellion united a multinational group of enslaved people from Louisiana, the French Caribbean, and West African polities like Asante and Kongo against shared oppression. This motley yet determined force drove east along the Mississippi toward New Orleans, then a walled territorial capital where blacks outnumbered whites, runaway Maroons and hostile Spaniards haunted the borderland bayous, and the French Creole citizenry distrusted their greenhorn American governor. Led by two Africans, Kook and Quamana, and an enslaved overseer from Saint Domingue named Charles Deslondes, the insurgents toppled plantations like dominoes; as whites fled en masse to the capital, they left their land defenseless. It cannot be proved that this force planned to abolish slavery, as had their Haitian predecessors. But the historian Vincent Brown, a Harvard scholar who has written extensively on slave rebellions, told me it would be “a dereliction of historical duty” not to imagine their unrecorded aims.

Armed planters and American dragoons massacred the rebels, driving those they couldn’t capture or kill into the swamps. One year later, Louisiana joined the union, opening the Mississippi River Basin to a century of plantation slavery and genocidal conquest. By order of the governor, the rebels were tried and executed on the plantations they’d overthrown. Their decapitated heads were displayed on pikes along River Road.

The few public reminders of the antebellum era take the form of tours at refurbished plantations. Visitors to estates like Destrehan, one of the plantations where the rebels were tried and executed, vicariously indulge in the sweet life of planter aristocrats. Destrehan does have a small exhibit acknowledging the uprising—arguably the most important event in the property’s history—but it is housed in an outbuilding and omitted from the main tour. The focus is on period ambience, the furniture, clothes, and intimate passions of lordly patriarchs whom docents often refer to with avuncular affection. Mannequins, permanently engrossed in their domestic labors, are the most prominent representations of the enslaved. In 2015, domestic terrorist Dylann Roof took selfies with a similar display months before he shot nine black congregants at the Emanuel A.M.E. church in Charleston, South Carolina.

“Just imagine going to Auschwitz and hearing about the commandant and his difficulties,” Scott said as we passed the San Francisco Plantation, now a tourist attraction, in Garyville. “Nobody would accept that.” The big house sits squarely in the middle of an immense Marathon refinery. San Francisco, like many of the area’s extant plantations, was renovated by big oil, and today its website advertises availability for weddings: “Imagine stepping back in time when sugarcane was king, and money didn’t matter.”

Facebook forced to remove content internationally, EU court rules (The Verge)

The European Court of Justice came to its decision after an Austrian politician, Eva Glawischnig-Piesczek, requested an order that would force Facebook to remove comments that were “harmful to her reputation.” Glawischnig-Piesczek argued that Facebook should remove the comments and limit access to them worldwide. The court ruled against Facebook, dealing a heavy hit on tech companies as lawmakers and platforms continue to discuss how to regulate online speech.

“EU law does not preclude a host provider like Facebook from being ordered to remove identical and, in certain circumstances, equivalent comments previously declared to be illegal,” the court said in a statement. “In addition, EU law does not preclude such an injunction from producing effects worldwide, within the framework of the relevant international law.”

In its ruling, the European Court of Justice affirms that companies like Facebook and Twitter are not liable for the content posted on their platforms, but that exemption does not prohibit the courts from ordering the companies to take down illegal content. Late last month, this same court ruled that Google doesn’t need to remove links taken down from “right to be forgotten” requests worldwide. But illegal content can be limited internationally, according to Thursday’s Facebook ruling.

Related: Huge "Police Lives Matter" Facebook page run from Kosovo, pushed misinformation about U.S. cops (Popular Information)

Related: Facebook says Trump can lie in his Facebook ads (Popular Info)

Related: Twitter exec for Middle East is British 'psyops' soldier (Middle East Eye)

Francis May Not Change the World. But He Is Reshaping the Church (NYT)

In a ceremony at St. Peter’s Basilica on Saturday, Francis will create 13 new cardinals who reflect his pastoral style and priorities on a range of issues, including migration, climate change, the inclusion of gay Catholics, interreligious dialogue and shifting church power away from Rome to bishops in Africa, Asia and South America. The new appointees among the cardinals will include prelates from Morocco, Indonesia, Guatemala and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

After Saturday, Francis will have named more than half of the voters within the College of Cardinals – where a two-thirds majority of those under the age of 80 are required to elect his successor – making it less white, less Italian and less representative of the Roman curia, the bureaucracy that governs the church.

The longer Francis lives, the more his pontificate matters.

By appointing cardinals and more than a thousand bishops on the front lines of the faith, Francis is reconstituting a church in his image. It is one that decentralizes power from Rome to the bishops around the world, that is willing to work through the challenges of the modern world together with other faiths, and with atheists.

While liberal critics argue he has not moved fast enough to reform the church — especially when it comes to the role of women — his supporters note that he is at the least willing to talk about and reconsider church policy on married priests, and its stance toward homosexuality and celibacy.

And tellingly for a pontiff with a tense relationship with conservative opponents in the United States, he has again passed over America’s traditional feeder schools for the College of Cardinals, especially those occupied by conservatives.

Father Czerny, a close collaborator of Francis, said the result of a College of Cardinals shaped by Francis was a willingness to take up difficult issues “in a way, in a style, in a spirit” consistent with the Second Vatican Council.

In Search of a Black Odysseus: My Father’s Journey Home (LitHub)

I empathize with Telemachus, the son who yearned for Odysseus’s return but then rejected it when it happened because he couldn’t recognize his own father. His father’s a liar, a deceiver, and was supposed to have been long dead, but, even if none of that were true, in the first book, when asked of his parentage, Telemachus declares, “My mother says indeed I am his. I for my part / Do not know. Nobody really knows his own father.” Paternity tests weren’t around in ancient Greece, of course, but here Telemachus seems to refer to fathers as unknowable in a more general sense.

In my poem “Telemachus,” which comes late in the book, I write, “Fathered by rumor, raised / by ghost, you’ve learned // to love the slimness of the shadow from which you grew.” Telemachus’s moment of incredulity feels real to me. No one wants to hold onto absence when it’s taking the place of someone you love, but that ironic phrasing is important—absence does, in fact, have a place. Or, rather, one can always make a place of absence. It’s malleable, adaptable, and in that is comfort. You can build something new out of absence, build a whole home out of it, learn to love it, because you crafted it into the shape you needed most.

I loved the Greek stories, the epics, though I resented the protagonists: selfish, proud men who left their families behind to have new adventures. Some made it out well: Odysseus slaughtered the suitors and reclaimed his position as king, husband, and father; and Aeneas went on to become the first hero of Rome. Some didn’t do as well: after their adventures, Jason and Heracles both suffered sad, pitiful deaths. My father felt oblique to me, impenetrable, no less so after his death, so I molded his absence into the shape of the heroes I knew, from the stories that he taught me to love.

Pope Francis denounces countries that sell weapons but deny refugees (Axios)

"Wars only affect some regions of the world, yet weapons of war are produced and sold in other regions which are then unwilling to take in the refugees generated by these conflicts," Francis said. The solution, he said, was "being a neighbor to all those who are mistreated and abandoned on the streets of our world, soothing their wounds and bringing them to the nearest shelter, where their needs can be met."

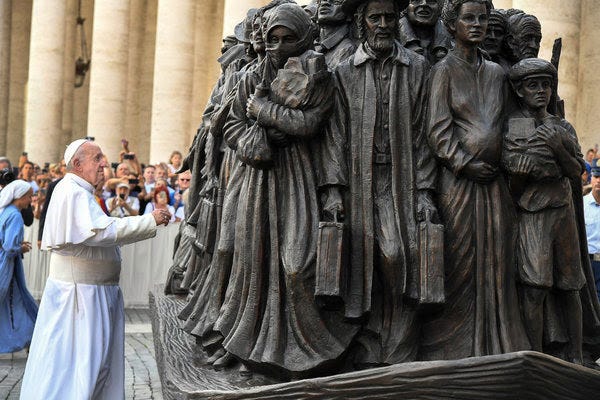

Of note: Pope Francis also inaugurated a statue in St. Peter’s Square depicting migrants and refugees from different faiths and different periods of history to mark the Roman Catholic Church's World Day of Migrants and Refugees.

Related: Pope Francis meets with Jesuit criticized for LGBTQ outreach (Axios)

Related: Pope Could Soon Approve Married Priests and Open a Schism (RCR)

Related: Pope Francis is Fearless (NYT)

SCOTUS Starts Next Week – Expect Fireworks on Abortion, LGBTQ Rights, and Immigration (Vox)

In Kavanaugh’s second term, the Court appears much less shy, going bythe cases it has agreed to hear. On Friday, the Court announced that it will hear June Medical Services v. Gee, a case that could well be the vehicle the Court’s conservatives use to gut the right to an abortion. Republicans are likely to win a big prize for their decision to muscle Kavanaugh through his confirmation hearing, a deep cut at abortion rights.

By next June, the Supreme Court alsoplans to decide whether federal law allows workers to be fired because of their sexual orientation or gender identity. It will likely let the Trump administration start winding down the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program that allows hundreds of thousands of undocumented immigrants to live in the United States. It plans to hear the first major Second Amendment case in nearly a decade (although that case may be dismissed for lack of jurisdiction). And looming on the horizon is a potential showdown over Obamacare.

Related: Disgraceful – Fired Because They’re LGBTQ (Human Rights Campaign)

Stop Getting Married On Plantations (The Nation)

Recently, The Washington Post published a story about the discomfort some white people experience during tours of antebellum mansions in the Deep South. “My husband and I were extremely disappointed in this tour,” wrote one online reviewer, noting that her family had never owned slaves. “We didn’t come to hear a lecture on how the white people treated slaves…. The tour guide was so radical about slave treatment we felt we were being lectured and bashed about the slavery…. I’ll go back to Louisiana and see some real plantations that are so much more enjoyable to tour.”

These thoughts upset me. I set aside the vexed question of “real plantations” for the moment, gently, so that I could better digest my soup.

My friends are right: I don’t relax. This history is too resonant in my body. It’s not easy for me to work up any kind of nostalgia for a style of life that depended on slaves, hierarchy, imperiousness, and pomp. And I frankly despise how the tourism industry has underwritten childish rituals of antebellum dress-up in crinoline and whalebone and marketed them as romantic, swoony, and gossamer.

I am no fun at all, I know.

Aesthetically, the antebellum plantations of the Old South are undeniably beautiful—flowering, gracefully constructed, with seemingly benevolent stretches of fields and lawns. But they’re built on human degradation, and so they live on as icons of romance premised on the fragile privilege of racial innocence, historical oblivion, and educational denialism. American schools do not teach our own history. We write much of it out of the grand narrative, gussying up the bad bits, playing down the sorrow. And then, in the spacious vacuity of mutual misapprehension, we butt heads, we bleed.

We stumble in circles, so close to one another and yet so far apart, locked out of the homes and neighborhoods that we forget we built together.

The Climate Justice Movement Must Include Decolonization and Anti-Imperialism (TruthOut)

Capitalism is destroying the future of the planet. It is time to defend indigenous people’s right to their land, rather than incarcerating and murdering them for protecting their territory against the interests of the ruling class. The struggle for climate justice cannot succeed if its only goals are a few policy changes to increase industry regulation.

The struggle for climate justice must include decolonization and anti-imperialism. Climate justice activists need to fight the seizure and destruction of indigenous lands, from Brazil to the United States to the Philippines, and for the freedom of Red Fawn Fallis and all indigenous water and land protectors. The growing movement for climate justice has succeeded in building powerful international networks of solidarity, but it is imperative that this power be directed toward a broader decolonial (and, necessarily, anticapitalist) struggle.

Separated by 185 years, Jackson’s and Trump’s executive interventions both sit at the heart of modern Native American life and history. Both concern sovereignty, a vitally important concept – at once clearcut and elusive – in the world of politics and states. It can be defined as the supreme right of a self-designated body of people to govern itself and control its territory and resources without outside interference – with the crucial caveat that it has to be recognised by others to be effective. Together, through these two actions, we can see something essential about the rights of Native peoples in North America, past and present. Jackson’s and Trump’s assertions of US power over Indigenous peoples call attention to their singular political status as nations within a nation, and they speak to the continuing Indigenous struggle for sovereignty. Treaties are the quintessential tool of international diplomacy, and the US has long practice of making them with the peoples whom it dispossessed from their ancestral lands through brutal and at times genocidal methods.

Emerging from the coalescing American empire and the rapacity of American capitalism, Indian Removal marked the erosion of Indigenous sovereignty east of the Mississippi Valley. It was the Lakota – a Native people that includes the Hunkpapa, the Minneconjou, the Oglala, the Sans Arc, the Sicangu, the Sihasapa and the Two Kettles – who mounted the longest and most comprehensive opposition to US expansionism. The riches promised by King Cotton fuelled a rapid and ruthless implementation of US control and sovereignty in the Black Belt, the part of the American South where geological processes left soils almost perfectly suited for cotton cultivation. In a striking contrast to the forced mass removal of Indigenous Southerners, the Lakota thwarted American imperialism in the West for generations, all the way to the Battle of the Little Bighorn.

To do so, the Lakota had to reinvent themselves as a formidable warrior society. Crazy Horse, Sitting Bull, Red Cloud and other iconic warrior-leaders embodied that transformation. That history is well-known. What has remained more obscure is how the Lakota mounted a nearly two-centuries-long campaign to preserve Indigenous sovereignty in the face of a US empire that saw them as wards and, when fighting and killing them, as internal enemies.

Twitter executive for Middle East is British 'psyops' soldier (Middle East Eye)

The 77th Brigade uses social media platforms such as Twitter, Instagram and Facebook, as well as podcasts, data analysis and audience research to wage what the head of the UK military, General Nick Carter, describes as “information warfare”.

Carter says the 77th Brigade is giving the British military “the capability to compete in the war of narratives at the tactical level”; to shape perceptions of conflict. Some soldiers who have served with the unit say they have been engaged in operations intended to change the behaviour of target audiences.

What exactly MacMillan is doing with the unit is difficult to determine, however: he has declined to answer any questions about his role, as has Twitter and the UK’s Ministry of Defence (MoD).

Twitter would say only that “we actively encourage all our employees to pursue external interests”, while the MoD said that the 77th Brigade had no relationship with Twitter, other than using it for communication.